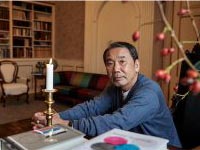

Haruki Murakami

Winner of the 2016 Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award

Haruki Murakami is a Japanese writer. He received the H.C. Andersen Literature Award in 2016.

About Haruki Murakami

Haruki Murakami claims that he learned to write novels by listening to music, and he refers constantly to the qualities of rhythm, melody, harmony, and free improvisation. His novels are quirky: surrealistic and supernatural, melancholic and fatalistic. They blend myth and modern, magical realism and traditional Japanese tales. He received the H.C. Andersen Literature Award in 2016.

Haruki Murakami (born 1949) is a Japanese writer. Both of his parents taught Japanese literature. Since childhood, Murakami has been heavily influenced by Western culture, particularly American and Russian music and literature.

He grew up reading a wide range of works by European and American writers, such as Franz Kafka, Gustave Flaubert, Charles Dickens, Kurt Vonnegut, Fjodor Dostoyevsky, Richard Brautigan, and Jack Kerouac. These Western influences distinguish Murakami from most other Japanese writers. His fiction has been heavily criticized by Japan’s literary establishment, who view his popular appeal and wealth of references to western culture with suspicion.

In addition to his original literary works, he has translated from English into Japanese works by writers ranging from Raymond Carver to J.D. Salinger.

His first job was at a record store, like Toru Watanabe, the narrator of Norwegian Wood. Later, Murakami opened a coffee house and jazz bar, which he ran with his wife from 1974 to 1981. At the age of 29, while attending a baseball game in Jingu Stadium, he was struck by the sudden epiphany that he could write a novel.

He wrote four novels before Norwegian Wood propelled the barely known Murakami into the spotlight in 1987.

His protagonists are almost always caught between the spiritual world and the real world, occupying a position at – or on both sides of – that boundary. He takes liberties with time and consciousness, but nothing is overwrought. Everything is understated.

His books and stories have been bestsellers in Japan and internationally. Nine novels, four short story collections, and two works of non-fiction are currently available in English translation. His work has been translated into 50 languages and has sold millions of copies, although the precise number has not been disclosed.

He has received numerous awards in Japan and internationally, including the World Fantasy Award (2006), the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award (2006), the Franz Kafka Prize (2006), and the Jerusalem Prize (2009).

Haruki Marukami's acceptance letter

The Meaning of Shadows

It was only recently that I read Hans Christian Andersen’s story “The Shadow.” My Danish translator, Mette Holm, recommended it, saying she was sure I would find it interesting. Until I read it, I had no idea at all that Andersen had written stories like this.

As I read the Japanese translation of “The Shadow,” I found it had an intense, frightening plot. Andersen is known to most people in Japan as a writer of fairy tales aimed at children, and I was astonished to find he’d written such a dark, hopeless fantasy. And a question naturally came to me, namely, “Why did he feel the need to write a story like that?”

The protagonist of the story is a young scholar who leaves his homeland in the north and travels to a foreign land in the south. There something unexpected happens and he loses his shadow. He is upset and confused, of course, but eventually he manages to cultivate a new shadow and return safely home. Later on, though, his lost shadow makes its way back to him. His old shadow had, in the meanwhile, gained wisdom and power and had become independent, and financially and socially was now far more prominent than its former master. The shadow and its former master had traded places, in other words. The shadow was now the master, the master a shadow. The shadow now falls in love with a beautiful princess from another land and becomes the king there. And the former master, the one who knows his past as a shadow, ends up being murdered. The shadow survives, achieving great success, while his former master, the human being, is sadly extinguished.

I have no idea what sort of readers Andersen had in mind when he wrote this story, but in it we can see, I think, how Andersen the fairy tale writer, abandoned the framework he’d worked with up till then, namely writing tales for children, and instead borrowed the format of an allegory for adults, and attempted to boldly pour out his heart as a free individual.

I’d like to talk about myself here.

I don’t plan out a plot as I write a novel. My starting point for writing a novel is always a single scene or idea that comes to me. And as I write, I let that scene or idea move forward of its own accord. Instead of using my head, in other words, it’s through moving my hand in the process of writing that I think. In those times I value what’s in my unconscious above what’s in my conscious mind.

So when I write a novel I don’t know what’s going to happen next in the story. And neither do I know how it’s going to end. As I write, I witness what happens next. For me, then, writing a novel is a journey of discovery. Just as children listening to a story eagerly wonder what’s going to happen next, I have the same exact feeling of excitement as I write.

As I read “The Shadow,” the first impression I had was that Andersen, too, wrote it in order to “discover” something. Also, I don’t think he had an idea at the beginning of how the story was going to end. I get the sense that he had the notion of your shadow leaving you, and used that as his starting point to write the story, and wrote it without knowing how it would turn out.

Most critics nowadays, and quite a number of readers, tend to read stories in an analytical way. They are trained in schools, or by society, that that’s the correct reading methodology. People analyze, and critique, texts, from an academic perspective, a sociological perspective, or a psychoanalytic perspective.

The thing is, if a novelist tries to construct a story analytically, the story’s inherent vitality will be lost. Empathy between writer and readers won’t arise. Often we see that the novels that critics rave about are ones readers don’t particularly like, but in many cases it’s because works that critics see as analytically excellent fail to win the natural empathy of readers.

In Andersen’s “The Shadow” we see traces of a journey of self discovery that thrusts aside that kind of easy analysis. This couldn’t have been an easy journey for Andersen, since it involved discovering and seeing his own shadow, the unseen side of himself he would want to avoid looking at. But as an honest, faithful writer Andersen confronted that shadow directly in the midst of chaos and fearlessly forged ahead.

When I write novels myself, as I pass through the dark tunnel of narrative I encounter a totally unexpected vision of myself, which must be my own shadow. What’s required of me then is to portray this shadow as accurately, and candidly, as I can. Not turning away from it. Not analyzing it logically, but rather accepting it as a part of myself. But it won’t do to lose out to the shadow’s power. You have to absorb that shadow, and without losing your identity as a person, take it inside you as something that is a part of you. You experience that process together with your readers. And share that sensation with them. That’s one of the vital roles for a novelist.

In the nineteenth century, when Andersen lived, and in the twenty-first, our own century, we have to, when necessary, face our own shadows, confront them, and sometimes even work with them. That requires the right kind of wisdom and courage. Of course it’s not an easy task. Sometimes dangers arise. But if they avoid it people won’t be able to truly grow and mature. Worst case, they will end up like the scholar in the story “The Shadow,” destroyed by their own shadow.

It’s not just individuals who need to face their shadows. The same act is necessary for societies and nations. Just as all people have shadows, every society and nation, too, has shadows. If there are bright, shining aspects, there will definitely be a counterbalancing dark side. If there’s a positive, there will surely be a negative on the reverse side.

At times we tend to avert our eyes from the shadow, those negative parts. Or else try to forcibly eliminate those aspects. Because people want to avoid, as much as possible, looking at their own dark sides, their negative qualities. But in order for a statue to appear solid and three-dimensional, you need to have shadows. Do away with shadows and all you end up with is a flat illusion. Light that doesn’t generate shadows is not true light.

No matter how high a wall we build to keep intruders out, no matter how strictly we exclude outsiders, no matter how much we rewrite history to suit us, we just end up damaging and hurting ourselves. You have to patiently learn to live together with your shadow. And carefully observe the darkness that resides within you. Sometimes in a dark tunnel you have to confront your own dark side. If you don’t, before long your shadow will grow ever stronger and will return, some night, to knock at the door of your house. “I’m back,” it’ll whisper to you.

Outstanding stories can teach us many things. Lessons that transcend time periods and cultures.

It is a great pleasure for me to receive the Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award. Even in Japan, for well over a century Hans Christian Andersen has been an important writer, widely read, and he has been a major influence in the lives of children. His name alone sparks a special feeling of intimacy.

I am very honored to receive an award named after such an illustrious writer. And I am also very grateful to all my Danish readers for faithfully reading my novels for so many years.

Thank you very much.

Haruki Murakami

April 2016